100 YEARS OF OXFORD’S HISTORY OF SCIENCE MUSEUM

100 YEARS OF OXFORD’S HISTORY OF SCIENCE MUSEUM

The first weekend in March will celebrate one of Oxford’s greatest and least known collections

Published: 29 February 2024

Author: Richard Lofthouse

Share this article

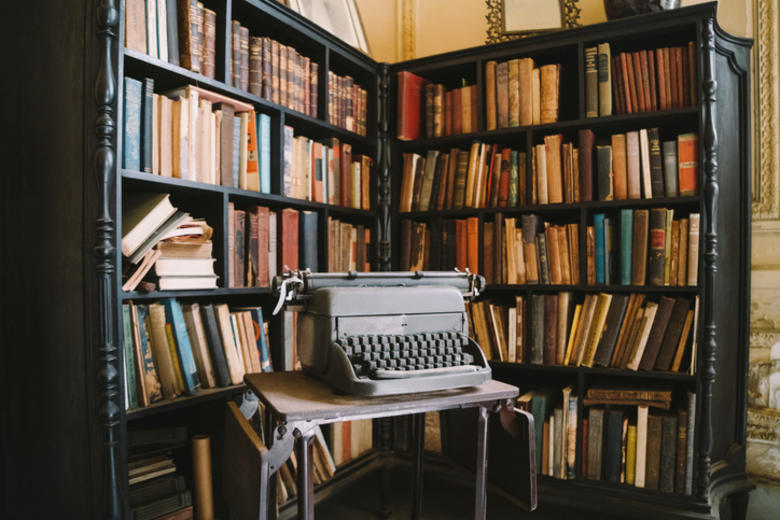

One of the intriguing details shared by History of Science Museum curator Dr Sumner Braund (Linacre, 2015) with QUAD, is that the beautiful building that today houses Oxford’s History of Science Museum right next door to the Sheldonian on Broad Street, was once Oxford’s chemistry laboratory.

The broader history of Oxford University as a great centre of scientific and medical research is less well known because the prevailing narrative in the Twentieth Century preferred classics and PPE and Prime Ministers, while Cambridge got the mathematics and sciences halo perhaps partly because it was the home of Sir Isaac Newton and Charles Darwin.

The Centenary of the dedicated History of Science Museum challenges that preconception.

It was a Fellow of Magdalen College Robert Gunther who carefully and determinedly won over the rest of the University, to dedicate a special building to a History of Science Museum in the Spring of 1924, the first in Britain.

The alternative course of action is that Lewis Evans’ remarkable collection of scientific instruments, manuscripts and books might have instead gone to the Ashmolean, the preference of the then Ashmolean Keeper Sir Arthur Evans.

But modern science was rapidly emerging as a dedicated, specialised galaxy of disciplines and Gunther won the day. We have much to thank him for, and his foresight demonstrates what one determined individual can achieve in a setting like Oxford.

Lewis Evans became a scholar in his own right but was never a student at Oxford. Instead, he was the Chairman of a prosperous family paper mill business and began to avidly collect scientific instruments, in particular astrolabes.

Astrolabes are multifunctional astronomical instruments and can be used to tell the time, to determine the length of day and night, to simulate the movement of the heavenly bodies, for surveying and for astrological purposes.

They continued to be used Mughal India and Persia well into the 18th Century because astronomical calculations were connected to cultural and religious occasions and festivals.

Elsewhere they may have been usurped by clocks and other mechanical instruments, yet continued to be status symbols valued by elites. Braund says, ‘these were social and political objects, and also works of art, made to be beautiful.’

She shows me a beautiful Persian astrolabe that Evans bought, and it far exceeds its utilitarian brief, being decorated with emblems and symbols and extraordinary to look at – the portal into a whole world of knowledge and philosophy and cultural belief, custom and practice.

This brass astrolabe, known as ‘The Hunter’s Astrolabe’ in reference to the hunting scene worked into its throne, was made in the 17th century in Persia, at that time rule by the Safavid Emperors (Shown Right, alongside correspondence by Lewis Evans).

To mark the 100th birthday occasion a programme of in-person, hands-on events and activities, for all ages, will take place on Sunday 3 March at the museum on Broad Street and across the road at the Weston Library.

Dr Braund, who is the John Fell Research Fellow, has researched the collection and redisplayed it magnificently, the big reveal taking place on March 2.

If we dig deeper, we are reminded that the current building was not only once a chemistry lab but had once been the first building of the Ashmolean Museum before it moved to its position on the corner of Beaumont Street and St Giles.

Dr Braund says, ‘This new display to mark the centenary will bring Lewis Evans’ passion to life and centre-stage, as well as inspire the next generation of scientists and collectors. Visitors will be able to see through his eyes – from the first spark of curiosity to founding the collection that created this unique museum – and appreciate his extraordinary role in establishing the first cultural space in the UK devoted to sharing stories with the wider public about the history of science.

Dr Silke Ackermann, Director of the History of Science Museum, said: “The History of Science Museum has, since 1924, been a wonderful place to explore how creative, curious people and their scientific achievements and ingenious solutions have, through the ages, addressed and answered the many questions we have about the world around us.’

Dr Ackermann adds, ‘Our ambition is to transform the museum into a more dynamic and welcoming space for generations to come so they can enjoy our collections, whether they walk through our door, or visit us online from wherever they are in the world.’

The Museum’s About Time curator, Dr Sumner Braund will be sharing her research findings at a talk in the Weston Library on Sunday 3 March at 3pm. Free tickets are available online.

About the History of Science Museum:

The History of Science Museum is the UK’s first museum dedicated to telling the story of the history of science and scientific discovery. The museum’s landmark site on Broad Street in Oxford is Grade I listed, and is the world’s oldest surviving purpose-built public museum. It is the original site of the Ashmolean museum, now on Beaumont St, dating from 1683.

Director Dr Silke Ackermann, the first female director of a museum at the University of Oxford, is currently leading a highly imaginative proposal to completely transform the museum. This ambitious project seeks to deliver fully accessible and inclusive displays, whilst also upgrading the historic building and preserving its heritage, to make it a dynamic and welcoming space for generations to come. Virtual tours and state-of-the-art digital content will be a part of the programme to provide ample opportunity for visitors to enjoy the Museum’s collections online, wherever they are in the world.