ALUMNI STORIES: ‘CLASSICAL MUSIC NEEDS TO BE MORE INCLUSIVE’

ALUMNI STORIES: ‘CLASSICAL MUSIC NEEDS TO BE MORE INCLUSIVE’

Des Oliver (Worcester, 2009) talks classical composing and how he thinks the industry needs to change

Published: 3 April 2019

Share this article

When did you first begin to feel an affinity with classical music?

I grew up in Bedfordshire and came to music relatively late. My first encounters with classical music were during my teenage years, singing in various choirs at my local state school, run by my mentor, Michael Baxter – a phenomenal musician and music teacher who sadly passed away a few years ago. I had a profoundly transformative experience in these choirs, and I knew then and there that I wanted to be a musician, to immerse myself in that magical world as often as possible.

I started playing the trumpet at 14 and within three years I’d passed my Grade 8 examination with distinction. Playing the trumpet opened up opportunities to perform in various ensembles: youth orchestras, concert bands, brass bands, and jazz bands.

I composed my first classical piece not long after taking up the trumpet. I refer to it as my first classical piece because prior to my encounters with this genre, I was passionate about hip-hop and convinced that I would be the next great rap artist. The piece was a duet for French horn and trumpet, based on a melody from a beginner brass instructional book. From what I can remember, it was a rather longwinded theme and variations; it wasn’t very good.

What were your early years like in the arts?

I did not come from a musical household but my mother was very encouraging. She brought me a cassette from the local jumble sale, a green and white tape that I still have: An Evening with Tchaikovsky – it was a selection of his symphonic movements and overtures. I spent hours in my room conducting these pieces, and by the time I was 15, I could conduct Symphonies 1-6 and the Manfred Symphony from memory.

I would switch between hip-hop, electro, and early house music to works by Haydn, Mahler, and Stravinsky. I think this diverse listening experience during my teenage years is partially responsible for my interest in exploring and drawing from music outside of the Western classical tradition today.

Looking back on those formative experiences, I’m always reminded of the challenges faced by music educators today. I’m a minority from a working-class background and I feel very fortunate that I had access to those opportunities. Today, in certain parts of the country, that isn’t always the case.

Having benefited from those wonderful experiences, I know how important it is to ensure future generations have access to those same opportunities. It’s vital not just because it’s a nice thing to do, it’s also important for the future of the music industry.

What inspires your music?

This is a question we composers get asked a lot. There is often a presumption concerning the causal arrow of the creative process: inspiration leads to creation. It’s an idea that has infected many young composers who believe that inspiration is something you wait for.

My inspiration comes directly from the act of doing, getting my hands dirty with sound: radiant harmonies, pulsating rhythms, and intriguing melodic cells yearning to be developed, and exploring the sonic possibilities within a glistening texture. For most composers, inspiration is a creative state that they need to work towards. For me, it’s more of a curiosity than a kind of divine revelation. It’s about asking, 'what would happen if I put X with Y?’, and being prepared for a surprising outcome.

There are recurring themes and subject matter that I find myself coming back to in my music. In more recent years, I've been drawn to ancient mythologies, and all my recent work reflects this. I wrote a symphonic ballet entitled Black Orpheus based on the 1959 tragic-romance film of the same name. I also set five choral odes from The Bacchae by the Greek tragedian Euripides, for large synthesised orchestra, live on-stage viola and actors, which was performed at the Oxford Playhouse for the OUCDS triennial Oxford Greek Play in 2017.

Credit: seb dows miller fourseventwo productions

Most recently, I composed a piece entitled Mallikāmoda for Hindustani vocalist Shruti Jauhari and the Oxford-based new music group, Ensemble ISIS. It was performed last year at the Holywell Music Room as part of the Music Faculty’s inaugural Sounds of South Asia Series concert. Mallikāmoda is the name of a female character who cries fragrant jasmine flowers that float along the Ganges River in the lesser-known fable from the Padma Purana, one of the eighteen major Hindu Puranas.

Later you came to Oxford for your DPhil in Music, what inspired that choice?

I studied piano and composition at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama and then received a scholarship to study with the composer Steve Martland at the Royal Academy of Music. My experiences at both conservatoires were invaluable in terms of working with performers, but I always felt frustrated by the lack of detail, especially in the areas of technique: theory, analysis, applied harmony, and orchestration.

Composers need to engage with practitioners, but we also need to explore in depth the underlying mechanics of music a little more than the average performer. Studying at Oxford gave me the opportunity to engage with musicologists, philosophers, mathematicians, and artists from beyond the world of classical music.

What are you working on at the moment?

I've just finished a 13-part documentary series showcasing the work of black British composers, commissioned by Sound and Music for the British Music Collection website, due to be released in March 2019. This was my first experience as a film maker. The project involved travelling across the country interviewing composers about subjects including the creative process, identity, and BAME representation in the arts.

I plan to write a string quartet with each movement dedicated to, and inspired by my encounters with, each of the four composers who feature prominently in the film: Tunde Jegede, Dominique Le Gendre, Daniel Kidane, and Philip Herbert.

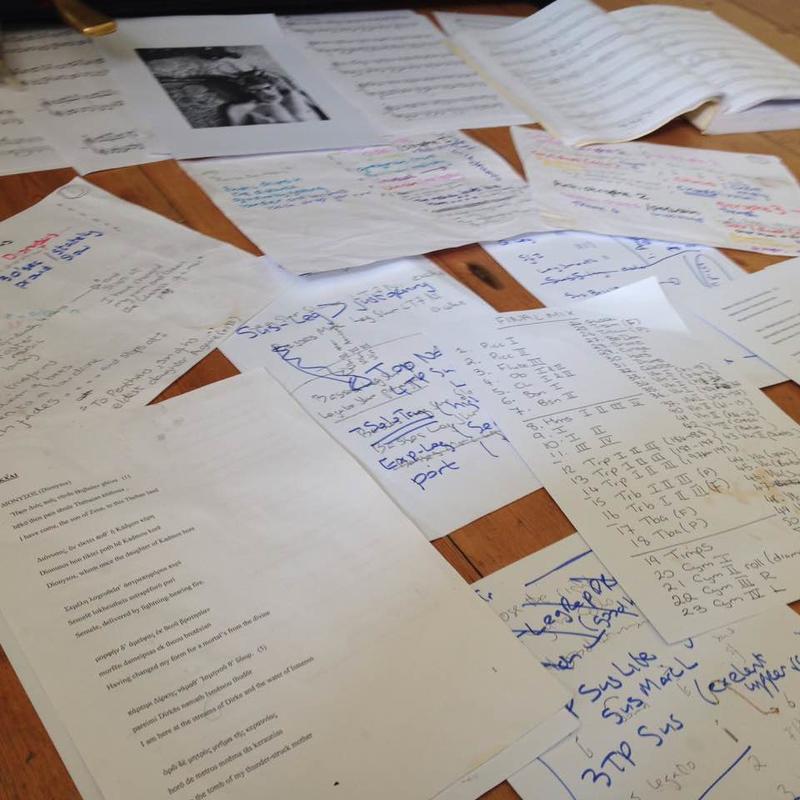

I'm also working on a chamber music version of my electronic piece Dionysian Rivers Flow Through Me for a female choir and chamber group, as well as solo work entitled Conversations for Double bass, which features briefly in my documentary.

Composers of art music dedicate an excessive amount of time applying for funding opportunities, so I spend a good portion of my days doing just that!

The world of classical music has traditionally been dominated by white males, how do you feel that’s changing?

It's a complex question that touches on issues of implicit bias, and the intersection between race and class; I'm unconvinced that it is changing fast enough. It was for this reason that I decided to make a film on black British composers, bringing to the fore their attitudes on BAME representation in the classical music industry.

Chi-chi Nwanoku (OBE) is the artistic director of Chineke!, who is Europe's first majority BAME orchestra, which is serving as a beacon for diversity in classical music. She has shone a light on the issue and inspired other major ensembles in the UK to follow suit, by investing in programmes that provide access to instrumental coaching. In 2016, the cellist Sheku Kanneh-Mason, protégé of Chi-chi and member of the Chineke! Orchestra, was the first black musician to win the BBC Young Musician of the Year award since its launch in 1978.

Another, perhaps more pressing issue for the industry is the aging demographic of concert-goers. This has left many professional orchestras competing for ever-decreasing audiences. There is a now a realisation within the industry that the decades of neglect of music education, particularly in state schools, is having a detrimental effect at the box office.

Another, less discussed aspect, was that in an attempt to widen participation at secondary-level, (during the 90s and 00s) a variety of styles from outside the Western classical canon were included in the syllabus. The thought, presumably, was the more diverse styles would encourage more diverse players that representation would lead to participation. But decreased funding and the rapid cessation of free peripatetic instrumental teaching in many areas has meant that fewer children have access to extra-curricular classical music. I doubt that this was ever the intention, but the reality is that it is more difficult today for children to access classical music training.

I fully recognise the necessity of genre representation; however, it is vital that we do not confuse the two. This is especially the case in diverse inner-city areas where there is often a presumption that if your cultural heritage is anything other than fully Western European or middle-class, then you are unlikely to want to participate in classical music, and many of us are living proof of that mistake.

What actions do you think can be taken to allow more diversity in the classical arena?

There is now a growing recognition that the repertoire within classical music needs to be more inclusive. Organisations such as Sound and Music – a charity that promotes new music by living composers – have pledged to achieve gender parity in their opportunities by 2020. There are classical composers from diverse backgrounds, we do exist, but we are painfully underrepresented in the repertoire.

What advice would you give to someone wanting to enter this area?

This question was addressed in one of my documentary episodes entitled Creative Pressures. The answer from all of the composers was very simple: time is a luxury; compose as often as possible, and make use of the time you have available, especially young composers currently studying music. Use this time to explore the untapped depths of your imagination and experiment with creative ideas as much as you can.

Do you have any favourite memories of your time at Oxford?

I spent most of my adult life living in London and when I was accepted on the DPhil course I decided very reluctantly to find a flat in Oxford. I was drawn to Jericho because of its architecture and its proximity to Worcester College. I'd visited several flats around that area but none of them had a wide enough entrance to accommodate my piano and studio equipment. The flat I eventually moved into had a very wide staircase with a stained-glass window located in the main hallway entrance on the first floor. The north-facing window held images depicting numerous colourful birds found in the fields and trees of Port-meadow. My thesis was on the 20th-century French composer Olivier Messiaen who was obsessed with birdsong and stained-glass windows. The first time I saw it I knew I'd found myself a new home.

But is wasn't just a pretty window, at the very top of the half round was the head of a colonial gentleman wearing a safari helmet, with a stern expression on his face denoting that he was an unrelenting disciplinarian. Just below this imposing figure was a tiny, rather frail-looking black hand holding a scythe blade just below his master's neck. The window looked out on to a street in Jericho called Plantation Road. One of the central themes of my thesis was cultural appropriation.

Did you have a favourite place/spot in Oxford?

I often set my prelim composition students a simple task when they arrive at Oxford. After our first session, I tell them to visit the Duke Humfrey's Library, to go downstairs to the lower-ground floor, and then walk through the long corridor (Gladstone Link) linking the Old Bodleian Library to the lower Radcliffe Camera reading rooms. A year into my DPhil, I stumbled across it almost by accident while searching for a book crucial to my thesis research, and it was like discovering the lost world of Narnia. I tell my students to climb the winding stairs to the top of the Radcliffe Camera and take the happiest selfie they’ve ever taken. I think the architectural design linking the old with the new is a nice metaphor for the Oxford experience. If you delve deeply enough to satiate your thirst for knowledge, you’ll come out the other end a much happier person!

In a sentence: what does Oxford mean to you?

My time at Oxford gave me the space I needed to truly find myself as an artist.

Des’ new documentary is available on the British Music Collection website now.