RADIOHEAD AT THE ASHMOLEAN

RADIOHEAD AT THE ASHMOLEAN

Oxford indie group Radiohead get a special exhibition at the Ashmolean Museum

Published: 6 August 2025

Author: Richard Lofthouse

Share this article

The one tension here is that you might know Radiohead very well or you might not know them at all. If the latter, go to this luscious exhibition with an open mind and see what sticks. If you’re one of the cognoscenti, you’ll likely geek out on the astonishing range of art and music narrative offered here.

The substantial catalogue accompanying ‘This is What You Get’ is produced to the same format as a vinyl LP cover, while you can actually make letter press prints of crying bear icons in the exit shop using a beautiful hand press from 1898, loaned by the Bodleian Library (Shown left; aping a medium used by Stanley Donwood, the principal artist of the show). As Ashmolean Director Xa Sturgis delightedly told assembled journalists at the media launch, with a twinkle in his eye, there is also an ‘eraser eraser’ you can buy – a pun on the 2006 album The Eraser.

But the clever merch comes at the end. The exhibition itself fizzes with art created over the best part of four decades by band frontman Thom Yorke and artist and friend Stanley Donwood, the two men having met as undergraduates at Exeter University.

Broadly, there are themes of angst aplenty, both on the emotional front and the environmental one, so the word ‘fizzes’ requires qualification. It has more to do with every varying media and constant experimentation, than euphoric vibes.

But dwell in the several galleries exhibited by the Ashmolean, and the art begins to speak its own rhythms, ‘encoded’ with the music as Donwood insisted once.

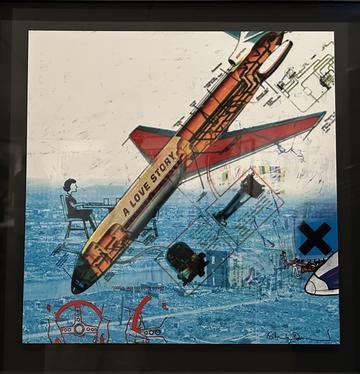

Take the 1995 Lucky Front, (right) a print of an airliner apparently plunging down towards a city that looks as if it has been flattened by a natural catastrophe or carpet bombing. Where you would normally see the airline brand name on the fuselage, it says ‘A Love Story’, suggestive of doomed romance but also a love affair with technology enhanced by bits of overlaid car driving manual, an inverted caption that reads, ‘Hand hold on the wheel.’

It sounds anything but jolly but this actual piece of art, when you look at it in the flesh, is full of modernist and colourist energies. The molten orange colour of the aircraft sets against the wan blue of the city below, contradicting Yorke’s mordant note that his ‘particular form of humour might be a new black pantone colour.’

Each gallery progresses from early albums such as The Bends (1995) and OK Computer (1997), to the striking, Los Angeles-derived word lists accompanying Hail to the Thief (2003), and then right through all sorts of much more recent creativity that might be unfamiliar even to people who thought they knew the oeuvre, such as Anima (2019) and A Light for Attracting Attention (2022).

We learn that the friendship blossomed over years, so that the two men would play contrived games often involving one erasing the work of the other whether through computer and mouse or actual pencil and tracing paper. There are fake marketing agencies to capture dreams half forgotten; there are snippets of manifesto but not really, as though the modernist project is well past the point of disbelieving itself; and by admission they often got part way with one thing ‘only to go off in another direction completely, lose interest and find something much more fun to do…’

The famous, might-be climaxing/might be dying dummy head featured on The Bends album was in fact a resuscitation dummy they dug up on a surreptitious rummage around a back room at the John Radcliffe Hospital in Oxford, cementing the local identity of a band that was always too quirky to conquer America.

Curator Lena Fritsch recounts that they had snuck into the hospital in search of an iron lung, except that finding one proved to be disappointing visually, it being in effect a metal box. But then they spied a resuscitation dummy, and put it through a complex series of still photos from a film reel, almost making it look like an Easter Island head but from the multimedia indie heights of 1995. Very cool and absolutely iconic.

There is a rough democracy to everything from the very beginning. Donwood admitted his intimidation in the face of art galleries, ‘whereas you can go into a record shop and its full of all kinds of oiks. It’s brilliant.’

If there is a risk to the exhibition it is the distracted, flitting quality of everything, driven evidently by ups and downs of commercial success and flop, critical attention good and bad, trying to follow one success with another; actual life lived off screen with its own intensities.

Yet – and this is a crucial saviour – you reach the big gallery and suddenly you’re confronted with large format paintings of intense, lush colour and it’s like: wow, that’s a bit unexpected. It’s a lift that requires no explanation, the impact enhanced because you’ve just come away from some very bleak pencil drawings of denuded landscapes where every tree has been cut to the stump, from Tomorrow’s Wooden Boxes (2014, Thom Yorke’s second solo album).

The colourful splosh in the big gallery (left) consists of artwork produced as recently as 2022-24, surely most of it unknown except to a hard core of fandom. From a simple art perspective it is possibly the most impactful here. Donwood had got fed up with computers but the real driver here was COVID-19 and lockdown, which, if you were a generally pessimistic, introverted creative, was by no means a catastrophe:

‘All of the political things that were going on did not have as much effect as a virus – that something as invisible as a virus could affect the whole population of the planet was sort of incredible – oddly made me want to make less miserable pictures.’ (Stanley Donwood)

Apparently the paintings, which employ tempera and gesso rather than the more normal acrylic, were influenced by a map exhibition they had seen at the Bodleian Library, another local reference; but in tone and feel they are landscapes described by Fritsch as ‘sentient and benevolent’. They are joyously colourful as though a psychic release had been achieved, when nature came to lower humans a peg or three, reminding us who is really in control of the narrative in the end.

Many people will want to know, ‘but can I listen to the music?’ Apparently neither Yorke nor Donwood wanted a scenario in which one track competes with another as you drift from one gallery to the next, a problem with other rock-tastic exhibitions of late. The compromise is twofold: headphones adorn walls and you put them on and press a button. But to a younger generation who might arrive with their own earbuds, a QR code sets up a more sophisticated sequence covering the whole exhibition.

This major exhibition explores the visual art of Stanley Donwood and Thom Yorke and the iconic images of Radiohead.

More than 180 objects are on display from the artists’ over 30-year collaboration, including original paintings for album covers, digital compositions, etchings, unpublished drawings, and lyrics in their sketchbooks. To date the band, which was formed in Oxfordshire in the mid-1980s, has sold 30 million records worldwide.

Developed and curated with Stanley Donwood and Thom Yorke, the show will offer a unique opportunity to look at the creative forces behind some of the most important and influential music of the past few decades.