WHEN OSCAR WILDE CAME TO OXFORD

WHEN OSCAR WILDE CAME TO OXFORD

Michèle Mendelssohn’s new book concerns Oscar Wilde in America, but his time at Oxford was a sort of dress rehearsal

Published: 17 July 2018

Author: Michèle Mendelssohn

Share this article

In 1910, Mills & Boon published The Romance of the Oxford Colleges and claimed that Oscar Wilde had been ‘a feature – an institution’ at Oxford when he was a student in the 1870s. Francis Henry Gribble, the book’s starry-eyed author, swooned ‘probably no undergraduate ever attracted more attention while still an undergraduate, or left a more enduring trail of legend behind him when he went down.’ If only. Gribble invented a myth about Wilde that had little basis in fact. Today, the legend still prevails. Yet the truth is that the witty playwright’s student days did not glitter with nearly as much stardust as some pretend. His afterlife has given him the legitimacy that life denied him.

Michèle Mendelssohn at the Oscar Wilde Memorial Sculpture in Dublin

Credit: Oxford University Press

When Wilde looked back on his life after he had become the toast of English society for his scintillating essays and The Picture of Dorian Gray, he said, ‘the two great turning-points in my life were when my father sent me to Oxford, and when society sent me to prison.’ He liked to pretend that it was at Magdalen College, on the banks of the Cherwell that his remarkable rise was set in motion. He did not care to remember how uncertain his social and professional fate had once been, nor did he mention that his academic success at Oxford had been assured from the start. Intellectually, it was to be an encore more than a beginning.

In fact, Wilde’s Oxford career properly began at Trinity College Dublin. It was there that he took his first degree in classics, scooping the Berkeley Gold Medal for Greek and a reputation as an excellent scholar. By all accounts he was academically successful but socially unremarkable. Classmates thought him as clever but mopey, uncouth and awkward.

All this was to change at Oxford – or so he hoped. He arrived the day after his twentieth birthday, to begin his second university career. It was autumn 1874. Like a fairy tale in which a young nobody becomes a somebody, it was here that he decided to focus on making his name socially. And what subject did he choose to read? Why classics, of course! It was the only course of study at Oxford, he said, ‘where one can be, simultaneously, brilliant and unreasonable.’

Michèle Mendelssohn at the Wilde Family home

Credit: Oxford University Press

In choosing classics once again, he was assured of academic success, and could focus on making his name. With the benefit of three years’ university training already, he was more widely read, mature and mentally prepared than those around him. Nevertheless, he liked to give the impression of precocity. He was coy when asked his age, which he would sometimes casually reduce by as much as four years.

Wilde rarely spoke of the major advantage he had over his English peers. By his own account, he wasted his Oxford years in mere ‘extravagance, trivial talk, utter vacancy of employment.’ At Magdalen, Wilde showed himself off by hosting cozy soirées enlivened by music, Venetian glassware, choice tobacco and gin-and-whiskey cocktails.

He enjoyed playing the exotic Irish outsider when it suited him. Despite his friends’ fascination with his brogue, it progressively disappeared. ‘I wish I had a good Irish accent,’ he said in later life, regretting the loss and explaining that ‘my Irish accent was one of the many things I forgot at Oxford.’

Wilde took his first steps towards fame, and slowly gained a reputation that spread beyond the student body to at least a few of the professors. A Balliol College don described him as ‘a brilliantly clever scholar, who had strangely good taste in art and in humanity.’

Then, in his last year as an undergraduate, he won the University’s Newdigate English Verse Prize for ‘Ravenna,’ a 332-line poem celebrating that northern Italian city’s great citizens. The award conferred membership to an elite circle of men. Matthew Arnold, John Ruskin and John Addington Symonds were among previous winners. They were also among the cultural giants on whose shoulders Wilde hoped to stand, one day. ‘I should so like to see the smile on your face now,’ his mother wrote from Dublin.

His graduation held a further surprise in store - a double First, an outstanding academic result. Wilde was just as surprised as his teachers. ‘The dons are ‘astonied’ beyond words,’ he said, about ‘the Bad Boy doing so well in the end!’

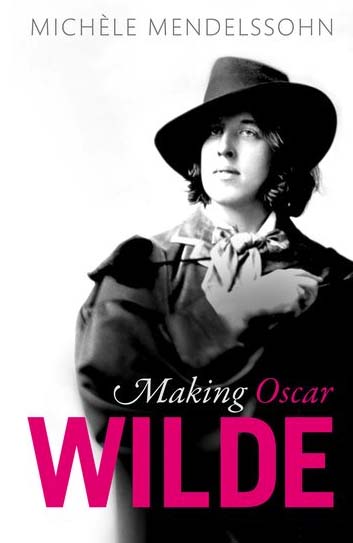

Making Oscar Wilde by Michèle Mendelssohn

Credit: Oxford University Press

None of this was any guarantee of success in the world. And though he had his fair share of notoriety, so did other students. There were many University men who commanded attention because of their specialness. For example, Wilde’s contemporary, Christian Cole of Sierra Leone, was one of Oxford’s first black African graduates. Known as one of the ‘Great Guns’ of Oxford, he was such a student celebrity that each spotting him counted as an event. One young lady recorded sighting him in her diary —twice. Sadly, Cole’s biography is still omitted from most University histories. Still, it goes to show that there were starrier undergraduates against whom the Irish aesthete had to compete for attention.

Wilde’s career did not immediately bloom after Oxford. ‘I’ll be a poet, a writer, a dramatist. Somehow or other I’ll be famous, and if not famous, I’ll be notorious,’ he told friends. He set about trying all these careers in turn (and a few more besides). He curried favour among those who might be able to help him, dividing his attention between prominent figures in education and art. On one occasion, he offered his services as a personal shopper with an excellent taste in neckties. For all his hustling, he was hardly making a living, let alone making his name.

Michèle Mendelssohn, Associate Professor of English, Mansfield College, Oxford

Michèle Mendelssohn is a literary critic and cultural historian. She is Associate Professor of English Literature at Oxford University. She earned her doctorate from Cambridge University and was a Fulbright Scholar at Harvard University. Her previous books include Henry James, Oscar Wilde, and Aesthetic Culture and two co-edited collections of literary criticism, Alan Hollinghurst and Late Victorian Into Modern (shortlisted for the 2017 Modernist Studies Association Book Prize). She has published in The New York Times, The Guardian, African American Review, Journal of American Studies, Nineteenth Century Literature, and Victorian Literature and Culture.

Michèle Mendelssohn’s new book Making Oscar Wilde is published by Oxford University Press.